Dunmere

The Dying Heart of Ebonmoor

We’ve tilled this land since our fathers' fathers walked it. We’ve raised cattle so strong they could weather the worst winters. But now? Now they rot on their feet, their eyes black as the Blight itself. The rivers still flow, the fields still stand, but I swear by the Old Ways—something in Dunmere has turned against us."

— Jorwel Kaelssen, cattleman

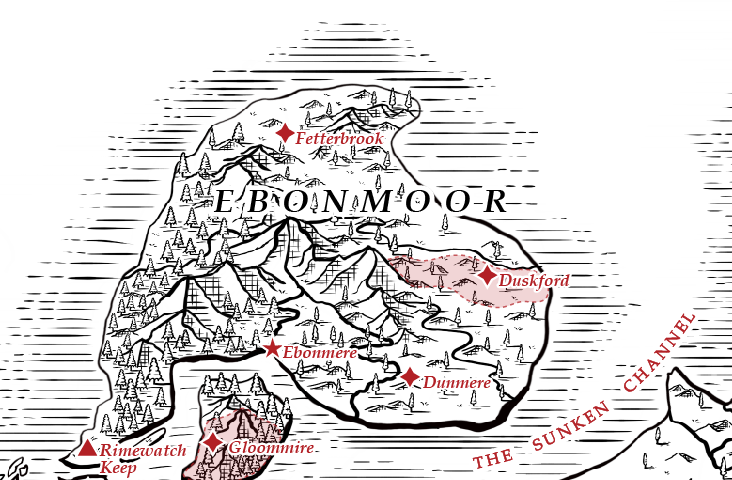

Dunmere was once the Breadbasket of Ebonmoor, a town built on the lifeblood of its fertile fields and strong rivers flowing from the Grimholt Peaks. It was a place of stability, prosperity, and abundance, where the cycles of planting, harvesting, and butchering dictated the rhythm of life rather than war or famine. Its golden wheat fields stretched as far as the eye could see, and its rolling pastures were thick with fattened cattle and sturdy hogs, raised for generations by families who took pride in their craft. The Kaelssen, Bronstad, and Hegerholm clans were among the most respected, known for breeding the healthiest livestock, their herds famous across Norvostra for the quality of their meat and resilience to harsh winters.

At the heart of Dunmere stood the Stonehall Market, a vast, open-air trading hub where farmers, butchers, and merchants bartered and sold their goods. The scent of freshly baked bread, roasted meats, and earthen spices filled the streets, and traders from as far as Mistvale and Blackvale made the journey just to secure the finest cuts of beef and pork. The town’s butchers were renowned, not just for their skill in carving meat but for their deep understanding of preservation, seasoning, and smoking techniques, ensuring that Dunmere’s meats were coveted even in lands beyond Faulmoor. During the autumn harvest festivals, the town would transform into a place of joyous revelry, with great feasts, music, and competitions where young ranchers showcased their prize-winning cattle and bakers competed for the title of the finest loaf.

Dunmere’s people were proud but welcoming, a mix of hardworking farmers, seasoned herders, and skilled tradesmen who valued tradition and community. Unlike the tense nobility of Valkenheim or the shadowed dealings of Greymire, Dunmere had no taste for intrigue or politics. It was a town of honest work and simple joys, where families passed down the knowledge of the land from one generation to the next. It was said that a man in Dunmere could be judged by the quality of his fields, the strength of his livestock, and the generosity of his table, and guests were always greeted with a hearty meal and a tankard of thick, honeyed ale.

Duskford, Dunmere’s sister town, served as its gateway to the wider world, with its bustling river docks sending barrels of salted pork, dried beef, and fresh grains to Blackvale and beyond. The two settlements thrived together, one feeding the region, the other ensuring its bounty reached those in need. Their connection was more than economic—it was personal. Many families had kin in both towns, and marriages between Dunmere’s herders and Duskford’s traders were common, strengthening the bond between them.

But when the Rotmire Blight took Duskford, that bond was severed in an instant.

Those who escaped fled to Dunmere, carrying nothing but desperation and grim determination. Yet, unlike the aimless refugees wandering other parts of Faulmoor, these people knew what was at stake. Many had once worked the fields or tended livestock, and instead of waiting for aid, they threw themselves into rebuilding Dunmere. Fields were expanded, irrigation systems improved, and new livestock enclosures erected in a desperate effort to secure food for Ebonmoor. They saw Dunmere as the last true stronghold of agriculture, the only hope for their people. But time was against them—while the crops flourished, the demand for food had tripled, stretching their resources to the limit.

Then came the sickness. It did not strike the people, but the livestock. At first, it was subtle—cattle grew restless, refusing to eat or sleep, their eyes wild with fever. Then the signs became clearer: veins blackened beneath their skin, their bodies bloated overnight, and some rotted from within, dissolving into a foul-smelling sludge that even carrion birds refused to touch. Dunmere’s butchers slaughtered thousands in an attempt to stop the spread, but the sickness persisted, creeping through the herds like an unseen shadow. No living person in Dunmere showed signs of the Blight, yet the symptoms mirrored it too closely to ignore. Fear gripped the town, for if the sickness could take the livestock, it was only a matter of time before it found its way into human flesh.

Rumors spread like wildfire. Some claimed the rivers from the Grimholt Peaks carried a hidden corruption, poisoning the land with every flood. Others believed the soil itself had turned, that the Blight had seeped into the earth and taken root. There were those who blamed the air, saying the Rotmire’s breath had begun to spread even where no undead walked. And then there were the voices of superstition and dread, whispering that this was punishment—that something older than the gods had cursed them for failing to save Duskford. No one knew the truth, but everyone understood one thing: if Dunmere’s livestock failed completely, there would be no saving Ebonmoor.

Recognizing Dunmere’s absolute importance, House Wilthorne and its vassals fortified the roads between Dunmere and Duskford, constructing multiple small forts and heavily guarded checkpoints along the key routes. Soldiers patrol the perimeter, searching for any sign of Blight encroachment or potential threats. These defensive measures have slowed travel, but they are necessary—if Dunmere falls, there is nowhere left to retreat. The fall of Dunmere would not only doom Ebonmoor but likely Faulmoor itself. Without its food supply, the region would collapse into chaos, leaving Ebonmoor defenseless and the survivors of Faulmoor with no means of sustaining themselves.

With its famed meat industry on the verge of collapse, Dunmere’s once-thriving butcheries now stand half-empty, their salted reserves dwindling dangerously fast. The town still produces grains and vegetables, but without livestock, they cannot sustain Ebonmoor’s needs. Food shortages have led to rising tensions—some have turned to smuggling, hoarding food for personal profit, while others grow increasingly hostile toward outsiders and traders seeking to take what little remains. Though Dunmere is still governed under Eadric Wilthorne, control has largely fallen to a council of farmers and butchers, led by Jorwel Kaelssen, an aging but respected rancher. He fights to keep Dunmere stable, but the cracks are showing.

Dunmere is not lost—not yet—but time is running out. If the sickness cannot be stopped, if the food supply continues to dwindle, Ebonmoor will not survive another year. The people of Dunmere work with desperate urgency, but beneath their resolve lies a growing fear. They know the truth that no one dares speak aloud: it is only a matter of time.

Detailed Overview

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Region | Ebonmoor |

| Ruling House | House Wilthorne |

| Population (Before Blight) | ~1,500 (A thriving agricultural town, vital to Ebonmoor’s food supply) |

| Population (After Blight) | ~2,800 (Influx of Duskford refugees who immediately went to work on the farms, knowing the survival of Ebonmoor depends on them) |

| Major Industries | Farming, livestock breeding, butchering, grain storage, and food distribution |

| Primary Exports | Wheat, barley, vegetables, beef, pork, dairy products, and preserved meats |

| Current Ruler | Lord Eadric Wilthorne (oversees from Ebonmere, but local control is handled by the Farmers' Council, led by Jorik Kaelssen) |

| Government Type | Feudal rule under House Wilthorne, though de facto governed by a council of farmers and butchers due to the town’s crucial role in survival |

| Defenses | Multiple small forts and heavily guarded checkpoints between Dunmere and Duskford, patrolled by soldiers of House Wilthorne to prevent Blight contamination and secure food transport |

| Notable Features | Stonehall Market (once a bustling trade hub, now a tense center of food rationing), Kaelssen Ranch (largest cattle and hog farm, now struggling with livestock sickness), The River Gate (main waterway access, suspected source of contamination), Salted Hoof Butchery (once a thriving meat shop, now eerily quiet), The Farmer’s Keep (council hall where decisions are made about rationing and livestock culling) |

| Status | Critical condition. Crops still grow, but the unexplained sickness among livestock is rapidly depleting meat supplies. Smuggling is on the rise, and tensions between farmers, soldiers, and merchants continue to escalate. If Dunmere falls, Ebonmoor—and possibly Faulmoor—will collapse. |

Notable Establishments

Stonehall Market

At the heart of Dunmere lies Stonehall Market, once a bustling hub where farmers, ranchers, and butchers gathered to sell their goods. The scent of fresh bread and smoked meats once filled the air, and traders from all across Faulmoor came to buy Dunmere’s famous beef and pork. Now, the market has become a place of rationing and conflict. With food supplies dwindling, every transaction is filled with tension and suspicion, and disputes over portions are common. Smugglers move through the crowd in the shadows, and some claim that corrupt traders are skimming off supplies for their own profit.

Kaelssen Ranch

Once the pride of Dunmere, Kaelssen Ranch was the largest and most respected livestock farm in the region, owned by Jorik Kaelssen. Generations of ranchers raised strong cattle and hogs, their herds famous for their quality and resilience. Now, it is the epicenter of the livestock sickness. The enclosures reek of death as cattle collapse overnight, their veins blackened with disease. Workers burn entire herds to prevent further contamination, but the sickness persists. Whispers spread among the ranch hands—this is not a natural plague. Some believe the land itself has turned against them, while others blame the waters of the Grimholt Peaks for poisoning their herds.

The Salted Hoof Butchery

Once the finest butcher shop in Dunmere, The Salted Hoof was known for its masterful cuts, smoked meats, and salted provisions. It supplied merchants as far as Blackvale, and its owner, Erik Lothsen, was considered one of the most skilled butchers in Faulmoor. Now, the shop barely operates—livestock is scarce, and what little remains is diseased. Lothsen struggles to keep his doors open, but behind the counter, he is quietly supplying smugglers, selling what he can to those willing to pay in silver. Though many suspect his dealings, no one has the proof to accuse him outright.

The Farmer’s Keep

The Farmer’s Keep was once a communal hall where Dunmere’s ranchers and farmers made decisions for the town’s prosperity. It was a place of unity, where disputes were settled fairly and the future of the settlement was planned with care. Now, it is a site of arguments and desperation, as the Farmers’ Council, led by Jorwel Kaelssen, struggles to keep order. Every day, tough decisions must be made—which herds to cull, how much grain to ration, and who should be prioritized for food. Some farmers argue for greater military protection, fearing an attack from raiders or starving refugees, while others insist that the true enemy is within—those hoarding supplies for personal gain.

The River Gate

The River Gate is the main access point to Dunmere’s water supply, fed by the great rivers of the Grimholt Peaks. For centuries, this water nourished the fields and sustained the livestock, but now, it has become a source of fear. Many believe that the sickness spreading through Dunmere’s animals originates from the water, though no one can prove it. Some farmers have begun sealing off parts of the river, refusing to use its waters, while others continue out of necessity, hoping the sickness is nothing more than rumor.

The Last Harvest Tavern

A grim shadow of its former self, The Last Harvest Tavern was once the beating heart of Dunmere’s social life. Farmers and cattlemen gathered there after long days of work, sharing tankards of thick, honeyed ale and laughing over stories of past harvests and great cattle drives. Now, the laughter is gone. The ale flows slower, and the conversations have turned to fear, suspicion, and grim predictions. The owner, Maren Hegsdottir, struggles to keep her doors open, but behind the bar, she has begun hoarding grain, fearing that soon, even she will not have enough to eat.