Fenmire Overview

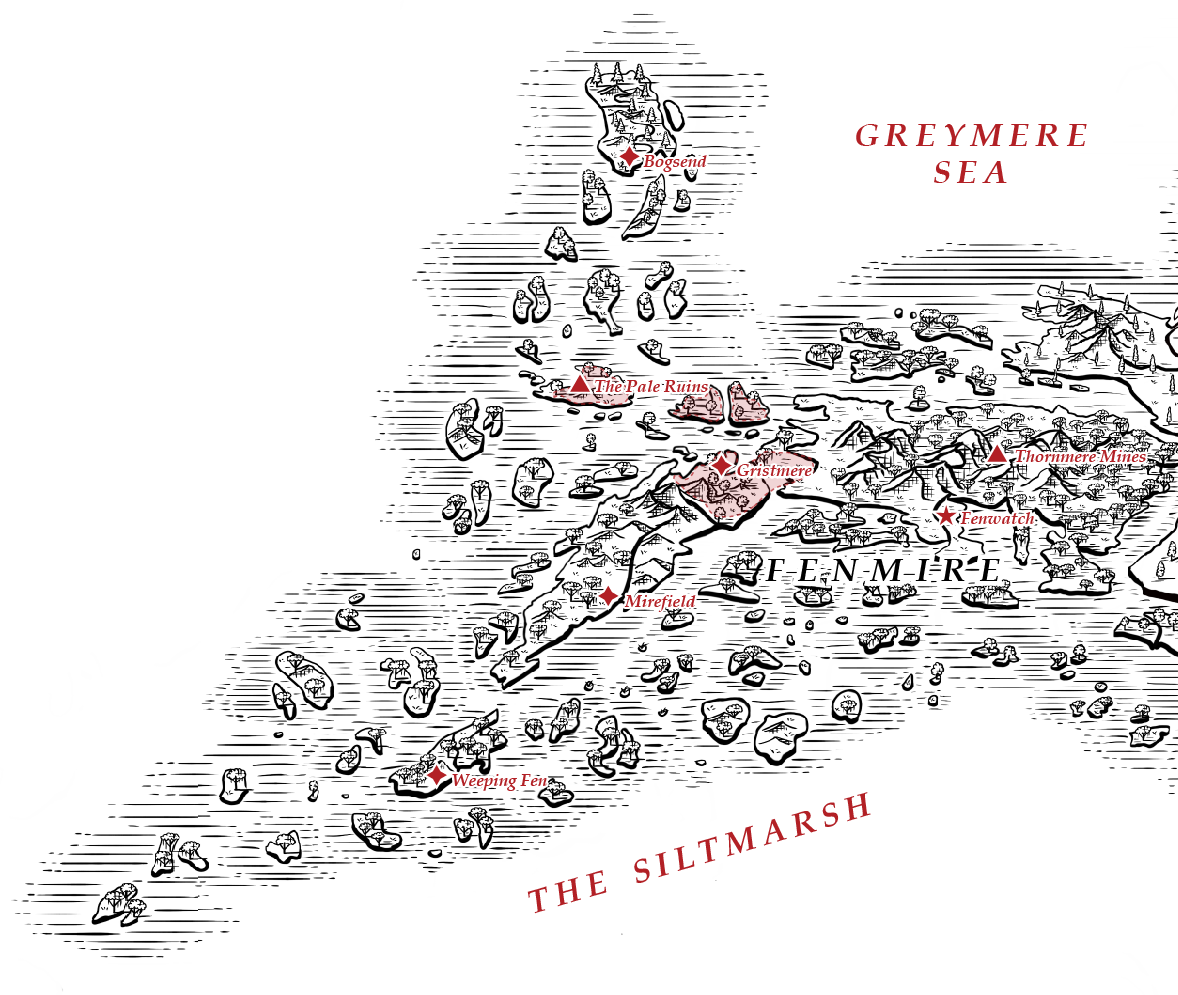

Fenmire, the most forsaken region of Faulmoor, is a vast expanse of deep bogs, brackish fens, and mist-choked waterways stretching toward the Greymere Sea. The land is half-drowned, characterized by sinking peat, twisted mangroves, and decaying reeds, making travel treacherous. Villages, when they can be built at all, are precariously perched atop raised wooden platforms, stilts, or half-sunken ruins from ages past, a patchwork of resilience against a land that does not welcome habitation.

The air is thick with humidity, heavy with the stench of damp rot, stagnant water, and the faint sour tang of decay. Even at midday, low, curling mists slither through the trees and rise from the bogs, obscuring vision and muffling sound. At night, pale green wisps—known as swamp lanterns—flicker through the gloom, playing tricks on the eyes and luring the unwary deeper into the marsh. The land is old—far older than the noble houses and their tenuous claims. Half-buried stonework and shattered obelisks rise from the muck, the remnants of a civilization lost to time. Fenwatch, the only semblance of a seat of power, was built upon what was once a mere trading post, growing as necessity demanded rather than through any true design. Its structures, reinforced with salvaged stone and water-resistant timber, stand as the closest thing to permanence in a place where the ground itself shifts beneath one’s feet.

Yet even here, the Blight and isolation take their toll. With the fall of Gristmere, the arteries that once connected the settlements of Fenmire to the outside world have all but collapsed. Mirefield, ever loyal to House Harrowden, has turned inward, fortifying its walls and blocking the old mountain passes in a desperate attempt to keep the horrors of the marsh at bay. Those who once relied on roads now cling to precarious ferries, hopping from island to island in an effort to keep trade routes open. It is a system that works for now, but the waters are unreliable, and Weeping Fen’s silence has only deepened the growing sense of dread.

The marshfolk endure because they must. They are an insular people, pragmatic to the point of cruelty, for in Fenmire, generosity is often the death of both the giver and receiver. They travel not by roads, for there are none, but by pole-boats and rafts, navigating the dark, reed-choked waterways where the land itself conspires against them. Food is hard-won. The soil is too poor for farming, forcing them to survive on fishing, foraging, and trapping. Yet even this has become dangerous. The waters, once teeming with life, now churn with things better left undisturbed. The fish, once the lifeblood of Weeping Fen, have grown sick, twisted by the same affliction that now grips the land. Thornmere Mines, the only true source of wealth in Fenmire, still bleed silver, but at great cost. Rumors persist that the mines have been exhausted, yet House Harrowden tightens its grip, unwilling to relinquish control of what little remains. The mines are heavily guarded, not just against would-be thieves, but against the growing number of desperate souls who would risk anything for a glimmer of silver, a chance at escape.

Some seek refuge elsewhere. Bogsend, despite its name, has become one of the last safe havens, a rare place of solid ground where deserters and survivors alike have banded together to outlast the coming collapse. They call themselves free men, but they operate under the grim belief that when the world finally crumbles, they will be the only ones left standing. They are self-sufficient, yet not above taking what they need from others. Smuggling has become their currency, their lifeline. They look upon the rest of Fenmire as doomed.

Doomed or not, the land still holds its secrets. Weeping Fen was built on old bones, its people unknowingly raising homes atop something long buried. The deeper they dug, the more they uncovered—walls too smooth, steps leading nowhere, carvings too precise to be the work of ordinary hands. No one thought much of it until the silence fell. No ships. No scouts. No trade. No sound but the whisper of reeds in the wind and the name of something unknown—The Last God.

The Pale Ruins stand in eerie contrast to the rest of Fenmire. Though partially submerged, they remain intact, untouched by time in a way that defies explanation. Before the Blight, pilgrims and mystics traveled there, swearing they could hear the voices of the gods in the wind. Now, those who go searching for relics return changed—if they return at all. And beneath the mire, beneath the ruins, something stirs.

House Harrowden does not rule Fenmire. They endure it. Their hold on Fenwatch is tenuous, their influence fraying. Once seen as necessary, they are now viewed as a burden, a force that takes without giving. Since the Blight, they have grown paranoid, destroying bridges, severing land routes, cutting themselves off in a misguided attempt to preserve what little they have left. Their soldiers, once enforcers of the Baron’s will, are now nothing more than well-armed scavengers, taking what they need under the pretense of law. Their lord, a man once dismissed as a brute, is now feared for his ruthless pragmatism. He does not care for honor, nor for politics—only survival.

Fenmire is lawless. The noble house that claims it cannot rule it, and the marshfolk know it. The strong take what they need, the weak vanish into the mire, and in the end, the swamp takes everything. The Blight festers here, different than elsewhere. It does not consume—it lingers. The infected do not turn immediately but rot, weep, and swell with stagnant water until the marsh swallows them whole, or worse, until they rise again. The land takes what it will, and now, in its depths, something older than kings and sickness watches and waits.

Fenmire is dying. But it does not die quickly.