Fenmire Overview

The Mire That Hungers

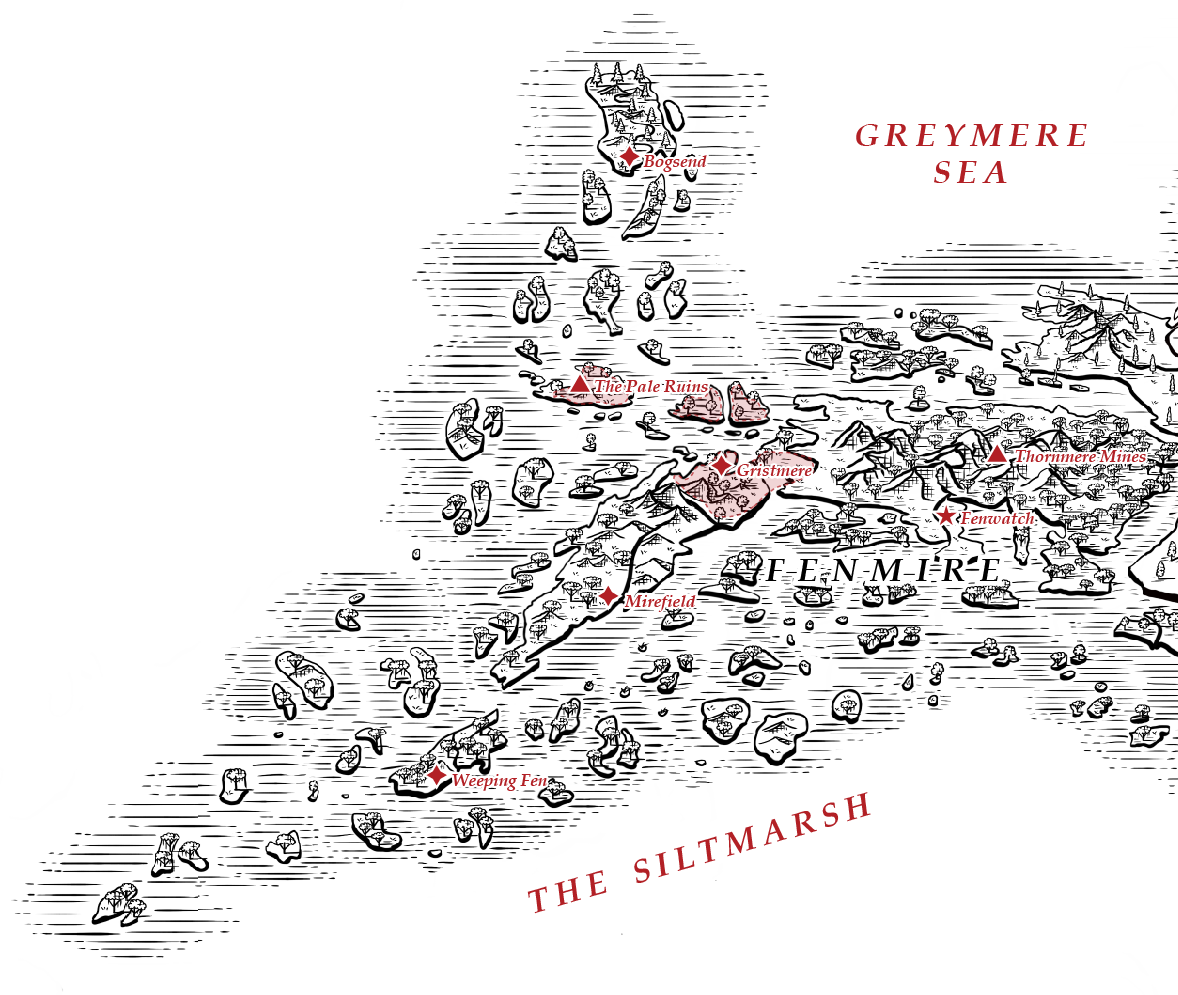

Fenmire is the most forsaken region of Faulmoor, a vast, tangled expanse of deep bogs, brackish fens, and mist-choked waterways that stretch toward the Greymere Sea. The land itself is half-drowned, a shifting mire of sinking peat, twisted mangroves, and decaying reeds that makes travel treacherous. Where the soil is firm enough to build, villages are precariously perched atop raised wooden platforms, stilts, or half-sunken ruins from an age long past.

The air is thick with humidity, heavy with the stench of damp rot, stagnant water, and the faint, sour tang of decay. Even in the height of day, low, curling mists slither through the trees and rise from the bogs, obscuring vision and muffling sound. At night, pale green wisps—known as swamp lanterns—flicker through the gloom, playing tricks on the eyes and luring the unwary deeper into the marsh.

Fenmire is an old place, older than the noble houses and the kingdoms that now squabble over it. The land is littered with ruins—half-buried stonework and shattered obelisks—claimed by the mire centuries ago. Some say these remnants belong to a forgotten empire, others claim they mark the graves of something far older. Whatever the truth, those who seek to unearth Fenmire’s past rarely return.

To live in Fenmire is to endure. It is to rise each day knowing that the land itself resents your presence, and that survival is not granted—it is stolen from the jaws of the swamp. The people of Fenmire, known as marshfolk, are a hard, insular people—superstitious and deeply distrustful of outsiders. They do not waste words and rarely offer help freely, for charity in Fenmire is often the death of both giver and receiver. They are accustomed to hunger, sickness, and hardship, but they are not weak. Those who cannot fend for themselves are lost to the marsh, one way or another.

Settlements are small and spread thin, often built along narrow riverways or upon high ridges of solid ground. The buildings are made of waterlogged timber, woven reeds, and clay, with roofs thatched from dyed moss or dark straw. Wooden walkways and rope bridges connect homes, keeping them raised above the ever-present water.

Few roads exist here. Instead, the marshfolk travel by pole-boat or raft, navigating the winding, reed-choked waterways with long wooden poles that sink deep into the blackened muck. Those who must travel on foot rely on narrow boardwalks or well-worn trails that skirt the worst of the sinking bogs. Stray too far, and the mire will claim you.

Fenmire has little in the way of farmland. The soil is too wet, too acidic, and too poor for traditional crops, forcing the marshfolk to eke out a living through fishing, foraging, and trapping.

Fishing is a way of life, but the waters are treacherous. The Greymere Sea is unpredictable, and the deep marsh hides things beneath the surface that should not be disturbed. Trappers hunt the strange and twisted creatures that call the swamp home, their skins and bones traded for coin in the few markets that still stand. Herbalists and alchemists prize the rare plants that grow only in Fenmire’s depths, from luminescent fungi to hallucinogenic swamp blossoms. Silver from Thornmere Mines is the only true wealth of Fenmire, and even that is cursed with blood.

Despite these industries, hunger is constant. The marsh gives little and takes much, and those who cannot find enough to eat often vanish in the night—either taken by the Blight, lost to the marsh, or given to whatever lurks in its depths.

There are no safe places in Fenmire, only places that are less dangerous than others. The land shifts underfoot. What is solid ground one day may be a sucking bog the next. Sinkholes swallow entire homes, and the quicksilt pits—grey-black sludge that pulls victims under—are nearly invisible beneath the water.

The deep fen breeds monsters, creatures shaped by hunger and shadow. Pale gators with rotting flesh and too many eyes. Leechmen, with swollen, pulsing throats that whisper names in the dark. Worse still are the hollow walkers—tall, spindly things that move like men but wear the stretched skin of their victims.

The Blight has spread to Fenmire, though it does not burn through the land as it does elsewhere. Here, it festers. The infected do not turn immediately. Instead, they linger—rotting, weeping, and bloating with stagnant water—until the mire swallows them, or they rise in the night, hollow and hungering.

There are places in Fenmire that do not belong to mortals. Ruins where the air hums, and the shadows seem to move on their own. Places where whispers curl through the fog, promising knowledge or madness. Those who stray into these places often return changed—if they return at all.

House Harrowden does not rule Fenmire. It endures it, just as the marshfolk do. Though their seat of power remains in Fenwatch, their grip is tenuous at best. The marshfolk do not see them as lords, but as a necessary evil—useful when coin flows and supplies are plentiful, despised when hunger sets in.

Since the Blight, House Harrowden has grown paranoid and withdrawn. They destroyed their bridges, severing land routes and isolating themselves. Their soldiers, once seen as enforcers of the Baron’s rule, are now little more than marsh reavers—taking what they need from their own people to ensure their own survival.

The lord of House Harrowden is a bitter, uncivilized man, once seen as a brute but now feared for his ruthless pragmatism. He does not care for honor, nor for the politics of Faulmoor—only survival.

This has led to a dangerous, unspoken truth: Fenmire is lawless. The noble house that claims it cannot rule it, and the marshfolk know it. The strong take what they need, the weak vanish into the mire, and in the end, the swamp takes everything.

As the plague festers, Fenmire becomes more isolated, more desperate. The marshfolk turn inward, refusing to help outsiders unless it benefits them directly. Quarantine is impossible—the land itself is too vast, too fluid, and too uncharted to be contained. The infected are simply cast into the marsh, where they wander until they rot away.

Silver has become currency, but only among those who believe it can save them. Others hoard food, water, and weapons, believing these will outlast all else. Rumors spread of something moving in the deep fen—something older than the Blight, older than the noble houses, and far, far hungrier.

Fenmire is dying, but it does not die quickly. Like the swamp itself, it lingers, festers, and devours all who do not belong.